By Jeffery D Regan LPT RTR, Director of Physical Therapy OAM

In the last blog, we talked about definitions of tendonitis and tendinosis with the goal of, over the next two blogs, discussing how to rehab these two similar diagnoses. This blog will deal with the rehab of tendonitis. However, before we get to how to rehab, we need to know a little bit about what is going on at the cellular level with the tendon itself.

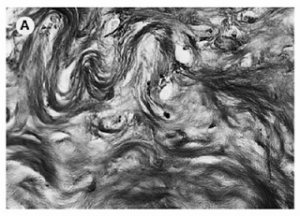

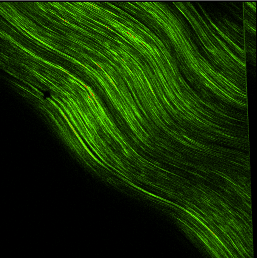

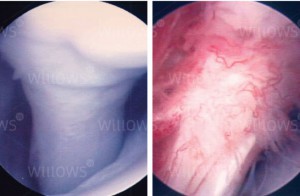

If you were to sustain a hit somewhere on your body with enough force, the point of impact would experience cell death and a micro-hemorrhage of torn capillaries. This trauma would then set up an inflammatory response in the body where vasodilation, clotting mechanisms, and white blood cells would be called upon to help the injured area. The problem is that this chemical chain of events doesn’t just “clean up” the injured area; unfortunately, it also eats/destroys the surrounding healthy tissue. So, if your injury is a small, one-time event, then it’s really no big deal, but, if it happens over and over again on a repetitive basis it becomes a real problem. The area begins to get inflamed; fibers from scar tissue cross bind to other healthy tissue and restrict freedom of motion. There is a loss of capillary beds in the tissue itself. Fluid from the inside of joint or tendon sheaths stops being produced and therefore, the sheaths lose their lubricating effect. Eventually, the healthy tissue is replaced with non-aligned, avascular tissue that has a reduced tensile strength. In other words re-injury and overuse of a joint experiencing tendonitis is likely to result in tendinosis; it’s the way the system is, unfortunately, designed.

Tendonitis has three phases

1. Acute Phase

2. Recovery/Rehab Phase 1

3. Rehab Phase 2/ Return to Sport

Acute Phase: Usually lasts one week or less (depending upon the mechanism of injury). This period is typically marked by the initial incident, such as a specific trauma or a bio-mechanical problem that has finally reached a maximum load. During the acute phase you need to combat the chemical reaction caused at the injured site. The use of ice, either packs or massage, is a good topical tool when applied to the region 3x per day. An ice massage (or ice water bucket) is should be applied to the area until numb for about 5-10 min. A thin towel may be placed between the ice bag and skin to increase comfort, but it will take longer to numb. All in all, ice helps reduce swelling and brings new blood to the area which helps keep scar tissue down and capillary vessels in the tissue viable. Other modalities such as heat, US and Estim have merit, but there is limited scientific evidence that they are highly effective. OTC non-Steroidal medicines are another good way in phase 1 to combat the chemical response of an injury. These must be used as directed and need to be continued over period of time to keep the concentration level in your blood stream to have any effect. If you use them “one and done” then they will have very little effect on the inflammatory cycle.

The next treatment is very low resistance exercise to keep the joint, above and below, the injury going and the surrounding muscles pumping. This should be done with low to no resistance. The last thing that I like to do is friction massage to the injured tendon. No matter what you do, scar tissue will form secondary to the inflammatory process and we need to align the fibers (which are usually random) with the longitudinal fibers of the tendon itself for tensile strength down the road. If we don’t, a weak point will form in the tendon and, when stressed again, it will more than likely fail meaning we will start again, from the beginning. Friction massage is a “dig and roll” motion at 90 degrees, perpendicular to the long axis of the tendon working from origin to the insertion on the muscle. Start out easy and gradually, over days, increase the pressure. 3-4 x per day x 5-10 min is enough. A recap of phase one is: Fix your cause. Ice. NSAIDS, if you are able. Low-load exercise. Friction massage.

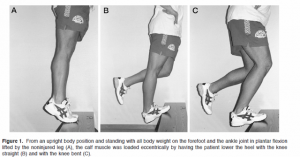

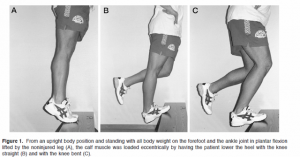

Recovery/Rehab Phase 1: The second phase can be started based upon your symptoms. If pain and swelling are reduced, and you are able to accomplish low-level function without an increase in symptoms, then the acute phase is done. Keep in mind that just because you have started phase 1 of rehab doesn’t mean that you stop acute phase treatments. You need to continue to use those tools to combat flare ups. The key to phase 1 of rehab is the addition of open Kenetic chain exercises in eccentric fashion to isolate and load the involved tendon, but exercise must be pain free.  Open Kenetic chain means that your feet and or hands are not attached to a solid non-moveable surface such as the floor. Eccentric means the negative part of the lift/ exercise lowering against gravity. These exercises allow isolation of the injured tendon/muscle, control the resistance applied, and focus it to the tendon itself. With this, we can build strength and endurance over the next two weeks (or as long as it takes to resume low-level activity without pain) by slowly adding resistance (weights) along with repetitions. The last thing I introduce is low-level stretching, along with all major muscle groups starting at 30 sec holds (no bouncing) repeating 2-3x and 2 time per day. The goal is to increase the intensity of the stretch each day, as long as only the stretch is felt and not pain. When the stretches and low-level activity are successful, you have graduated to phase 2 return-to-sport level. Remember, during phase 1 you may need to exercise the “other” muscles of your body so that it stays in good physical condition.

Open Kenetic chain means that your feet and or hands are not attached to a solid non-moveable surface such as the floor. Eccentric means the negative part of the lift/ exercise lowering against gravity. These exercises allow isolation of the injured tendon/muscle, control the resistance applied, and focus it to the tendon itself. With this, we can build strength and endurance over the next two weeks (or as long as it takes to resume low-level activity without pain) by slowly adding resistance (weights) along with repetitions. The last thing I introduce is low-level stretching, along with all major muscle groups starting at 30 sec holds (no bouncing) repeating 2-3x and 2 time per day. The goal is to increase the intensity of the stretch each day, as long as only the stretch is felt and not pain. When the stretches and low-level activity are successful, you have graduated to phase 2 return-to-sport level. Remember, during phase 1 you may need to exercise the “other” muscles of your body so that it stays in good physical condition.

Phase 2/Return-to-sport: Characterized by the continuation of the above, while adding close chain exercises and one plane drills at 50% of game intensity. Close chain exercises are those where your feet or hands are on a solid surface. Examples of this are Lunges, squats, pushups. These types of exercises are functional in that they create multi-planar contractions at many different joint levels along with many different types of muscle involvement and speed. For example, an athlete with patellar tendonitis who has been doing low load, high repetition leg extensions in Phase one, is now pain free and wants to return to soccer might start phase 2 with 4 inch quick steps (close chain and one plane) for 20-30 seconds x 3 reps at 50 percent, line hops with same parameters working front to back, side to side and diagonals. Balance/ proprioception exercises should also be introduced at this time to focus on the patient’s ability to hold joint posture, muscle co-contraction and know where his/her body is in space. When the athlete is able to perform these, along with other harder exercises at a 100%, its time to start a gradual return to sport at 50-75% of his/ her ability.

Start to finish, the process could be as easy as a couple weeks to as hard as months. In the next blog, we’ll move on to treatment of tendinosis.

Till then, keep your stick on the ice

Jeff

One of the initial benefits of Armor is the ability to book an appointment without needing a referral from your primary care physician. I was allowed 10 visits over a 21-day period which allowed time for an initial assessment, manual therapy, and rehabilitation as we sought approval for continual therapy. With each sports performance rehabilitation treatment I have sought with Armor over the years, initial diagnosis has been a lack of glute activation. My injury this time around was no exception. My hamstring and low back muscles were doing all the work and the nerves between the glute and hamstring were angry.

One of the initial benefits of Armor is the ability to book an appointment without needing a referral from your primary care physician. I was allowed 10 visits over a 21-day period which allowed time for an initial assessment, manual therapy, and rehabilitation as we sought approval for continual therapy. With each sports performance rehabilitation treatment I have sought with Armor over the years, initial diagnosis has been a lack of glute activation. My injury this time around was no exception. My hamstring and low back muscles were doing all the work and the nerves between the glute and hamstring were angry.